New Jersey native John Shoffner used to plan his vacations to North Topsail Beach around town meetings. Shoffner owns a condo on the north end of the island, but as a part-time resident he can’t vote in local elections. However, he’s allowed to speak during a meeting’s public comment period, and he wants a terminal groin on North Topsail Beach. “Since the beach started getting so bad, prices have been dropping like a rock,” Shoffner said. “I think I’m the only person in New Jersey who’s lost money on beachfront property.”

Topsail Reef homeowners including John Shoffner (far right), Jay Greenspan and Don Street. Photo credit: John Shoffner.

Shoffner bought his beach condo in 2007. The condo sits near the New River Inlet, the most erosion-prone area in North Topsail Beach. The inlet’s channel migrates south, cutting into the island’s north end. Shoffner and his neighbors protected their condos with a 12-foot sandbag wall, a last-ditch effort to stave off the shrinking shoreline.

Shoffner said the area needs something more stable than sandbags and beach nourishment. Trained as a mechanical engineer, he said when he sees something broken his first instinct is to fix it. “I understand the rules, and I admired the whole no-jetty thing,” he said. “But nobody is happy here. And we need something stronger than sandbags.”

The Topsail Reef condos in 2012, before the condo owners installed the sandbag wall.

Like Shoffner, close to 30 percent of beachfront property owners in Onslow County—where North Topsail Beach is located—live in other states. Shoffner said he’s always been frustrated by North Carolina’s hands-off attitude about the coast, especially the 30-year ban on hardened structures like jetties. “In New Jersey, we know the value of our beaches,” said Shoffner.

States like New Jersey and Florida use hardened structures like groins, jetties and seawalls to stabilize the shoreline. Groins are rock or steel walls that protrude anywhere from 250 to 500 feet from the shore toward the sea, trapping sand on one side. Like groins, jetties stick out from the shore, but they are longer structures built on both sides of an inlet to stabilize it for boat transportation. Seawalls stand parallel to the beach, protecting the property behind them.

According to a 2016 study in the Journal Bioscience, coastal cities like New York City have replaced more than 50 percent of their natural shoreline with hardened structures like seawalls. In total, 14 percent of the U.S. coastline has been hardened, according to the study.

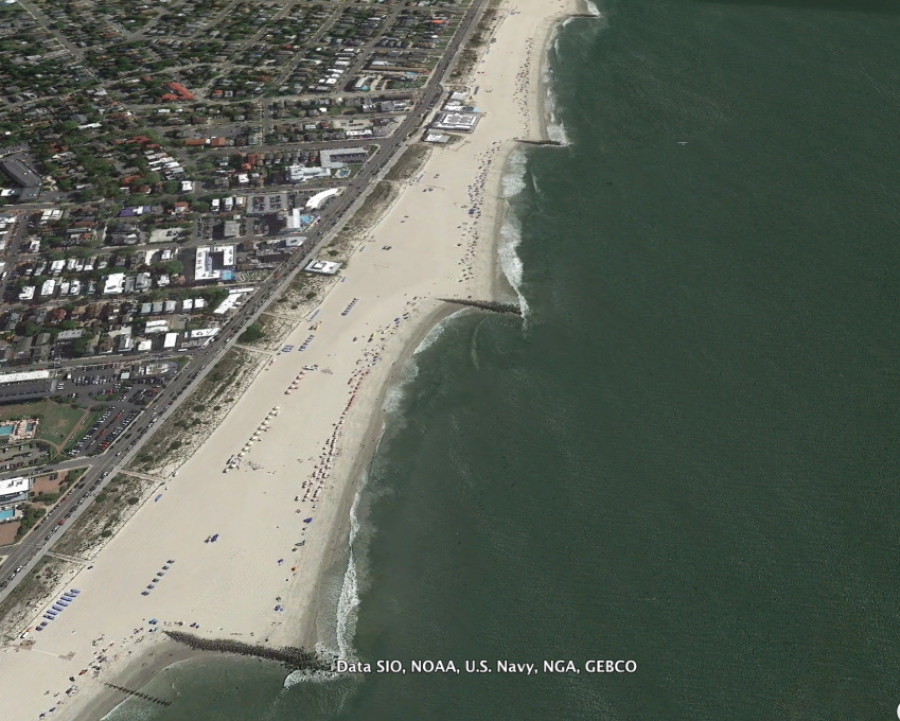

Cape May, New Jersey uses groins as sand traps. These “groin fields” interrupt the flow of sediment, worsening erosion down the beach.

Geologists say hardened structures are problematic on barrier islands because they disrupt the movement of sand. For example, groins trap sand, preventing it from replenishing other parts of the island. Seawalls protect property, but not the beach. As waves bounce against the wall’s unyielding surface, they drag sand from the beachfront. Seawalls also prevent the formation of mud flats and saltwater marshes in estuaries, essential habitat for breeding fish and wading birds.

North Carolina’s ban on hardened structures started as a statewide regulation in 1984 and became law in 2003, unanimously passed by the North Carolina General Assembly.

According to geologist Stanley Riggs, legislators banned hardened structures because there was widespread knowledge of their impacts. As a member of the Coastal Resource Commission’s (CRC) science panel since its inception in 1974, Riggs has advised policy planners on coastal dynamics.

“We were leaders in the country because we had agencies that respected the science,” he said. Riggs has studied coastal systems for five decades. Maps of the North Carolina coast cover his office at East Carolina University, where he’s taught and researched since 1967. “I’m a field guy,” he said. “I get my feet wet. I know what’s going on out there.”

Last year Riggs quit the science panel, writing in his resignation letter: “I believe the once highly respected and effective Science Panel has been subtlety defrocked and is now an ineffective body.”

In the last seven years, North Carolina’s policy has shifted to allow for more shoreline protection on barrier islands, especially near inlets. In 2011, the General Assembly lifted the hardened structure ban to allow four test groins near inlets. Four years later, the legislature added two more permits.

In addition, the CRC loosened restrictions on sandbag permits in 2016 by giving property owners more time to keep them in place if they add more bags or repair a section of the wall. The CRC also allowed sandbag walls to be placed in front of lots without structures. Sandbag walls act similarly to seawalls—they cause scouring and deplete the beach sand in front of them. “We’re on this collision course of more development, bigger homes and more demand to protect them,” said Riggs. “Unlimited growth just doesn’t work on a mobile pile of sand.”

The shoreline near an inlet erodes at a higher rate than other sections of an island. That’s because inlets swell and contract in response to storms and wave energy. The channel, or the deepest point of an inlet, can migrate, swallowing sediment on nearby banks. The inlet’s movements destabilize nearby homes. North Topsail Beach has lost 11 beachfront houses near the inlet. Holden Beach, another town next to an inlet, has lost more than 30 homes to shoreline erosion over the last two decades.

Inlets are rarely left in their natural state. Many, including the New River Inlet, are periodically dredged by the Army Corps of Engineers to allow for boat traffic. The Corps typically pumps the dredged sand offshore, where it is lost from the barrier island system completely.

“Almost every place that has inlet problems wants a groin,” said Andy Coburn, assistant director of the Program for the Study for Developed Shorelines (PSDS). “There has been a quiet effort by pro-development groups to get these things in place for years.”

In 2007, the General Assembly commissioned a report on the environmental and economic consequences of terminal groins. The study focused on groins in other states or those used for stabilizing historic sites like Fort Macon in North Carolina. The results of the study were inconclusive for some sites because the researchers couldn’t find erosion rates before and after the groins were installed. The sites with erosion data showed no clear trends. “Every inlet is different,” said Coburn. “We know there’s going to be impacts, but it’s almost impossible to say what will happen and when.”

Five towns alongside inlets have applied for terminal groin permits. Bald Head Island installed a terminal groin last year. Property owners on Figure Eight Island voted down a groin by a slim margin. Three more towns—North Topsail Beach, Holden Beach and Ocean Isle Beach—are putting together permits and proposals.

Riggs said inlets need “breathing room” to transport sand to the sound side of migrating barrier islands. Islands move toward the mainland as sea level rise gradually increases shoreline recession. In order to keep migrating, sediments have to wash over and around the island. Riggs said he worries that locking in an inlet with a groin will disrupt the process of rebuilding the island on the sound side, and islands will narrow and flatten as a result. “If you lock that system down, you’re going to lose it,” said Riggs. “If you have rising sea levels, you have to let the system work, or you’re dead.”

But Ken Willson of Coastal Planning and Engineering (CP&E), the firm responsible for many of North Topsail Beach’s erosion mitigation projects, said the proposed groin on North Topsail Beach won’t have far-reaching negative impacts. Willson said that unlike a jetty, which can extend more than 600 feet, groins aren’t long enough to disrupt the flow of sand. “It’s infuriating when people confuse groins with jetties.” he said. “They aren’t the same thing.”

Willson also said the law requires firms to fill the area behind the groin with sand. According to Willson, this would limit the amount of sand trapped by the groin and potentially counter the erosion caused by the groin in other areas. “Nobody in the engineering field wants North Carolina to look like the Jersey Shore,” he said.

North Topsail Beach has pursued a terminal groin since the ban was lifted. But with a general beach fund of a little less than $1 million, the town struggles to fund erosion control measures. According to CP&E, constructing the terminal groin will cost between $7 and $10 million.

North Topsail Beach mayor Fred Burns said he hopes a terminal groin will ease erosion issues on the north end. According to a 2010 study on terminal groins commissioned by the North Carolina General Assembly, the inlet’s movements on the north end threaten 136 properties, valued at $66 million. “The terminal groin will just slow that sand down and let it build on the north end,” said Burns. “And it will keep the inlet clear for boats.”

The engineering company’s recommended groin would extend 250 feet into the ocean roughly perpendicular to the shore. Mayor Burns said he’s hoping Onslow County and Camp Lejeune, the Marine Corps base across the inlet, will help fund the project. So far Onslow County has agreed to split the cost of an environmental impact assessment with the town.

North Topsail Beach’s proposed groin.

But Coburn said environmental reasons aside, the groin doesn’t make fiscal sense. He calculated that although at-risk structures on North Topsail Beach are valued at $66 million, they only generate $157,000 in property tax for the town. “Ninety percent of these oceanfront properties do not act as the owner’s primary residence,” he said. “Who’s responsible for protecting these people’s risky investment?”

Mayor Burns said many property owners in North Topsail Beach live full-time elsewhere, either in North Carolina or other parts of the country. As a result, he and other island leaders advocate for more state and federal support for shoreline protection through their lobbying group, the Topsail Island Shoreline Protection Commission. But Coburn said the groin would only benefit a few homes on the north end and the consequences aren’t fully understood.

“Sandbags were the start of this backdoor stabilization movement,” he said. “Once you open the door to allowing these structures, it’s a slippery slope. Someone in the middle of the island says, ‘Hey, why do they get one and we don’t get one?’”

Cameron Kuegel, a homeowner on the north end of North Topsail Beach said he isn’t worried about the possibility of more than one groin in the area. “The little budget we have will result in one little groin. I don’t think it’s going to create problems that can’t be handled.”

Kuegel moved to the area three years ago from Jacksonville, NC and quickly became involved in town political life. He said the town makes big decisions on shoreline protection during the winter. Often he’s the only attendee at town meetings. He posts frequently on the town’s “Save the North End” Facebook group, informing absent residents of the town’s decisions. Despite Kuegel’s support for the terminal groin, he doesn’t want to see North Carolina’s beaches become “engineered.”

“Once you start to over-engineer these beaches sometimes you’re left with nothing natural but the sunset,” he said. “Nobody wants that.”

But Riggs said he doesn’t have much hope that North Carolina’s beaches won’t become like those in New Jersey and Florida. “It’s a complex system and there’s no way to engineer your way out of it,” he said. “I don’t think my grandchildren will ever experience the beach like I did.”